A small post in the form of an artist’s biography as a teaser for the main post I will be releasing towards the end of this month! Spotlighting an artist who, in my opinion, is underrated in the canon of Italian Renaissance Art – Cesare Vecellio.

One of the most famous attributes of Cesare Vecellio is that he is a younger, second cousin of one of the most accomplished Italian Renaissance artists to come out of Venice, Tiziano Vecellio, otherwise known as Titian (or just Tiziano).

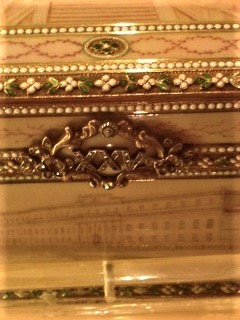

The Vecellio family came from Pieve di Cadore, a municipality in the Belluno region of the Veneto, and the birthplace of both Cesare and Titian. Not much is known of Cesare Vecellio’s life or artistic career, certainly not when compared to the wealth of biographical knowledge about the Venetian greats: Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese (who will all be the subjects of various posts in the future). Cesare possibly studied painting with Titian’s brother, Francesco Vecellio. He is thought to have joined the workshop of Titian himself sometime before 1548. By 1570, Cesare was no longer working in Titian’s workshop and was instead working primarily as a publisher, although paintings attributed to him, including portraits, are dated post-1570. Presumably, Cesare went to Venice to work in his cousin’s workshop, but it is unknown exactly when he arrived in La Serenissima. A significant event that is known in Cesare’s life is that he accompanied Titian on the older artist’s trip to Augsburg in 1548. Who knows what artistic influences Cesare Vecellio was exposed to during that time? Ultimately, this does not provide any further assistance in trying to identify painted works by Cesare. Some narrative works exist in churches around the Veneto that are considered indisputably to be the work of Cesare. A handful of portraits have been attributed to him, including one that will be the subject of my main post at the end of this month. He also published and drew the illustrations for several books, but the most notable, first published in 1590, was De gli habiti antichi et moderni di diverse parti del mondo. It had 420 woodcuts, most likely drawn by Cesare but printed by another artist, and followed up in 1598 with a second edition that had some 500 woodcuts. Both editions are still considered important artefacts in the study of the history of fashion and how different fashions were perceived in the Renaissance. Much of the scholarship on Cesare Vecellio has focused primarily on his costume and lace pattern books, but especially the two editions on the ancient and modern dress of the world, published in 1590 and 1598. Vecellio died in Venice in 1601. Image in the public domain. Page from De gli habiti antichi et moderni di diverse parti del mondo.

Image in the public domain. Page from De gli habiti antichi et moderni di diverse parti del mondo.

The above are the facts that exist (thus far, more could always be discovered in various archival sources) about Cesare Vecellio’s life. Some suppositions can be made based on these facts. He, like most other Venetian artists, probably created paintings on commission for families both in mainland Venetian territories and within the city of Venice itself. He most likely completed painted commissions outside of the workshop of Titian after he left. He was probably greatly influenced artistically by the works of Titian, but he most likely had his own artistic approach as well. Why leave his cousin’s workshop and continue painting, rather than just relying on publishing which was a lucrative craft in Renaissance Venice, if he was not also interested in continuing to be a painter in his own right? The lack of a significant number of surviving or attributed painted works does not mean he did not complete a greater number of painted works.

Next week’s blog post will be an object biography of Vecellio’s most famous costume books (both editions), and the main event at the end of this month will be an extensive, visual analysis of one of Cesare Vecellio’s (attributed) portraits, and also seek to explore some of the questions raised above.

Have any thoughts on this post, or Cesare Vecellio and his life & works? Please comment!

Sources:

Giorgio Reolon. Cesare Vecellio. La pubblicazione e stata realizzata. 2021

Cesare Vecellio. Vecellio’s Renaissance Costume Book: All 500 Woodcut Illustrations from the Famous Sixteenth-Century Compendium of World Costume by Cesare Vecellio. Dover Pubblications, Inc. 1977.

Eugenia Paulicelli. Writing Fashion in Early Modern Italy: From Sprezzatura to Satire. Routledge. 2016

https://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/online/Renaissance-Venice/Cesare-Vecellio

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/358319