The professor of a museum studies class I took during my Master’s taught us we can “ask” the same kinds of questions about objects as we would if we were interviewing people, and this can be a good way to discover the history of an object and how its use, perception, and significance has changed over time. I still use this any time I have to write about paintings and objects and I am applying it now to the portraits I am using as case studies for my dissertation. I won’t be talking about those portraits in this post, but I thought I would start an Object Biography series where once a month I do a deep dive into different kinds of objects (especially decorative art objects). So, you will be getting TWO posts a month (that’s the plan anyway. Except for October. I love Halloween and I have some big plans for this blog during October).

This post is based on the object biography I wrote for that class. The object I chose was one I was able to see in person at the Hillwood Museum, Estate & Gardens – the Iusupov music box (pink music box).

[All images were taken by me when I visited Hillwood].

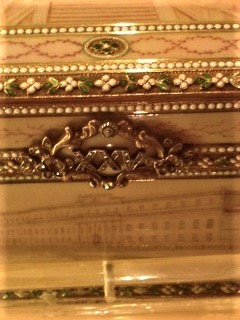

The Iusupov Music box was made in Russia at the Fabergé Jewelry company by one of their head craftsmen, Heinrich Wigström, around 1907. There are six main panels, one on each of the four sides as well as the lid and the base. There are two corner panels on the front of the box, featuring the letters F and Z, respectively, and two similar panels on the back featuring the letters F and N. Each panel on the box is made of enamel, done up in pinkish sepia tones. Gold banding, decorated with either a white and green enamel flower pattern, or a white enamel beading pattern, separates each panel. Each of the main six panels displays a different palace, and there are other, smaller panels featuring variations of a decorative branch pattern. The thumbpiece of the box is fashioned into the Roman numerals XXV (twenty-five), made of gold with tiny diamonds and two very small rubies on the center of gold flowers, one on either side of the thumbpiece.

It was commissioned by Feliks and Nikolai Iusupov (the F and N from one set of corner panels) for the twenty-fifth wedding anniversary of their parents, Prince Feliks and Princess Zinaida Iusupov (the F and Z from the other set of corner panels). The box plays “The White Lady” by François Boieldieu which was the march of Prince Feliks Iusupov’s regiment, the Imperial Horse Guards (Garde à Cheval). The six palaces represented on the box all belonged to the Iusupov family. The front panel shows their palace on the Moika in St. Petersburg (this palace would later become the scene of the murder of Grigori Rasputin in which Feliks Iusupov the younger was involved). The top panel depicts Arkhangelskoe, their summer palace near Moscow; on the base is their palace in Koreiz in the Crimea; the back panel shows their dacha (a traditionally decorated Russian house) at Tsarskoe Selo; the left side panel shows Rakitnoe in the Kursk province; and the right side panel shows their palace in Moscow. The images of these palaces are also good examples of pre-Revolutionary Russian architecture.

The music box’s life as a decorative art object did not stop with its original use as a wedding gift. It has since become an important representation of the history of Fabergé enamels, as well as the process of making enameled jewelry and decorative objects. Fabergé emulated the Louis XVI style for this box and used both the en plein enamel and painted enamel techniques and has become one of the best examples of the jewelry firm’s methods. It is also an excellent example of Fabergé’s use of a guilloched sunburst pattern. This involved etching lines on the metal surface, before painting on the enamel using different techniques. The engraving not only allowed the enamel to adhere better to the metal surface but could also add depth and dimension to the enameled scenes. Though this engraving process was common to the process of enameling, it was something the Fabergé firm would become well-known for. Fabergé was also known for pushing the boundaries when it came to enameled objects to try and get the best possible finished product possible. For instance, he was willing to risk exposing the pieces to seven- or eight hundred degree temperatures, instead of the established six hundred degrees that everyone thought was the safest temperature to set the enamel.

The journey of the music box as an art object also continued to change. The music box began as a personal gift from two siblings to their parents. At the same time it was considered one of the best, if not the best, example of the enameling talents of Fabergé and his master craftsmen. Looking at the time period the box was made in, as well as Russian history, it can also be inferred that this box would have been included in the greater collection of objects that was representative of the Russian royal family’s decadence and overt displays of wealth. About ten years after this box was made, the Russian Revolution happened and the Russian royal family was overthrown. Based on the reception of other, similar objects from the royal and upper class families by those who fought in the Russian Revolution, one can further conclude that this box would have been viewed as a symbol of that power and oppression by those who encountered it, especially as it displayed six of the palaces owned by the Iusupovs (they owned others), including one that was infamous as the scene of Rasputin’s murder.

The box is now a part of Marjorie Merriweather Post’s Russian Collection at the Hillwood House Museum. Here, it joins the history of her collection practices and the story of her life. It also has a new significance as part of a collection that is the largest collection of Russian Imperial objects outside of Russia. This beautifully designed music box began as a meaningful gift from children to their parents, became a symbol of a greater political history, and now represents not just the personal collecting history of Ms. Post, but also the history of Fabergé and of Russian Imperial objects.

Sources:

Odom, Anne. Fabergé At Hillwood. Washington, DC: Schneidereith and Sons, 1996.

Odom, Anne. Russian Enamels. London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 1996.